Nitrogen is one of the most important resources sustaining modern civilization. It is critical for plant growth and crop production. Despite constituting nearly 80% of the atmosphere, this form of nitrogen is unavailable to plants and must be fixed into a usable form by microorganisms. Some plant species, including legumes and Alnus species, have formed associations with microbial communities to fix nitrogen for them in exchange for nutrients and other benefits.

It’s for these reasons that pre-modern agricultural systems often included crop rotations where legumes were rotated with grain crops, along with periods where fields were left fallow or transitioned into grazing, where the manure from livestock would help replenish nutrients.

While these strategies are certainly present in modern production systems, they are much more optional than they used to be. If corn prices are high, you can safely forgo a year or two of soybeans. In older systems, this would have led to the collapse of yields and a winter of potential starvation. Pre-modern societies had strong circular systems of production and consumption, where all waste was recycled back onto the field where those nutrients could go back into the soil. This includes human waste. In some societies, economies and taboos around the collection and dissemination of excrement developed. In Japan, for instance, it was considered rude to eat at someone’s house and not use the bathroom before you leave, as that was seen as taking the fertilizer that farmer needed to produce food for the next year.

The modern history of nitrogen tends to begin in the early 1900s with two Germans — Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch. Haber, a chemist, and Bosch, an engineer, would pioneer a process that would come to bear their name, which allowed for the industrial fixation of nitrogen gas from the atmosphere into ammonia. From this starting point, a whole number of industrial products can be produced, but chief among them is fertilizer. This process is critical to sustaining our population of 8 billion. The caloric needs of a full third to a half of our planet would simply not exist were it not for the fertilizer this process produces. And for this, the Haber-Bosch Process consumes a full 1% of the entire energy output of our species.

It should be noted that the legacy of Fritz Haber, in particular, is often whitewashed in conversations about this stunning achievement of our species. Haber was not interested in the humanitarian benefits of this process but instead profited off of its destructive potential. He was a war profiteer who used this process to manufacture nitrate explosives for the Germans in WW1. I personally know less about Bosch, but my understanding is that he has multiple black marks in his legacy as well.

This is where the story of modern-day nitrogen use normally begins, with stereotypical European ‘Men of Science’ pushing the frontiers of what’s possible. And while this is certainly a chapter in this story, the beginning of the age of nitrogen actually begins on the coast of Peru with the mining of bird poop.

Note: Much of this post of based on the book Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History by Gregory Cushman. My focus is more on the direct agricultural and societal consequences of guano use, whereas Cushman dives more into the deeper sociopolitical consequences that said mining had for the Pacific world. I recommend his book for a much deeper dive if this post sparks any interest. I also draw from some of the scholarship of Vaclav Smil.

Guano fertilizer and early use

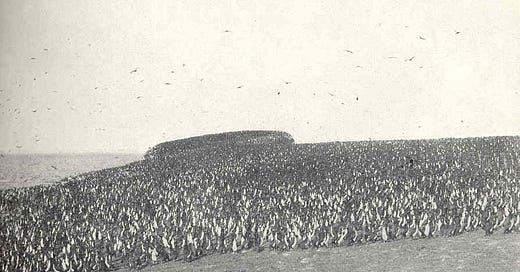

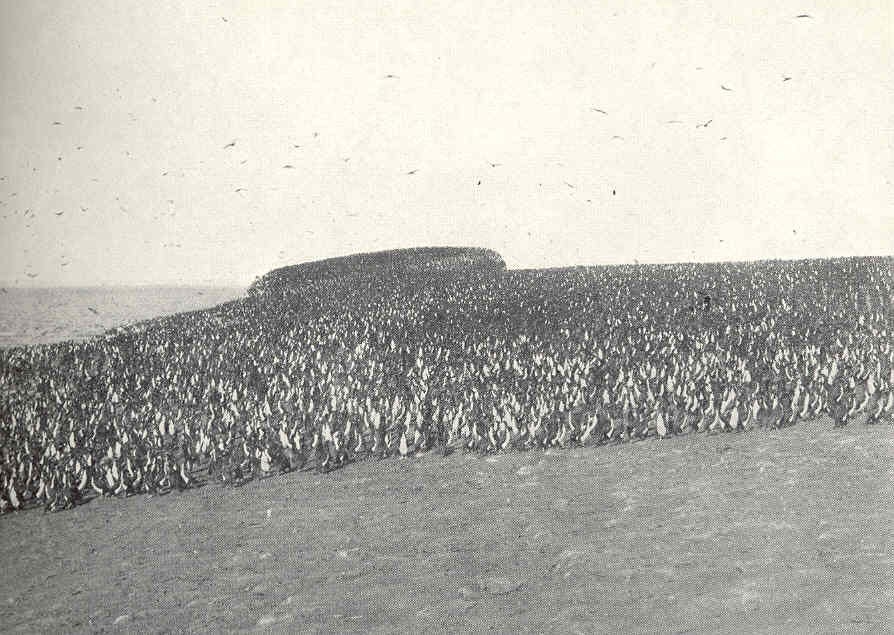

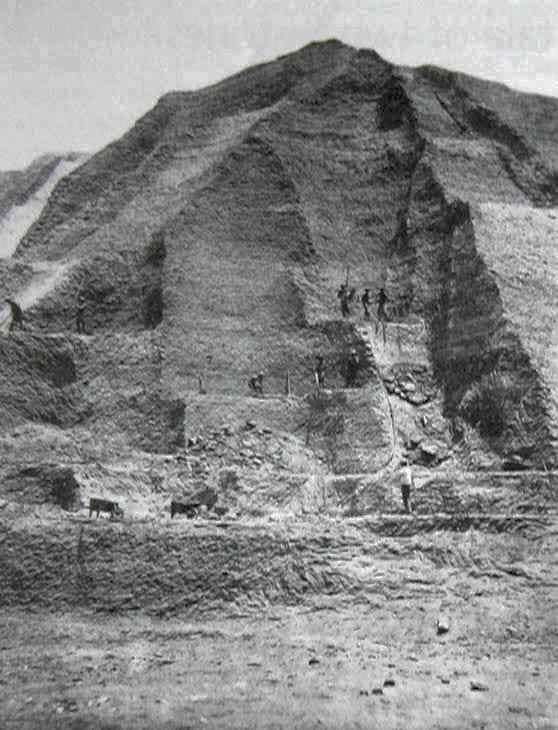

When we think of guano, we tend to think of it as a splatter of bird poop on the sidewalk, on our car windshield, or, if we’re having an unlucky day, in our hair. The guano deposits we’re talking about today are on an entirely different level. Most of the historic guano mining took place on the Peruvian coast, which due to its geography, had large populations of sea birds as well as intersected several bird migration routes. This blessing is compounded by teeming schools of fish living in the rich waters of the Humboldt Current, which provides these populations with a rich source of food, allowing them to produce copious amounts of excrement. On the rocky coastline and islands that served as ideal nesting grounds for these expansive colonies, massive amounts of guano accumulated over the millennia. Deposits meters thick were common. Below is an image of workers standing on a guano deposit. That entire mound is the accumulation of thousands of years of bird poop, dried into a soft rock-like structure.

Early settlers to the region, which by far has the richest guano deposits in the world, were quick to exploit this rich source of fertilizer. Though, they did so in way more in line with older ways of farming than our modern conventions. Instead of mining this resource to the bone, Andean peoples mined around the amount that was replenished every year. Part of this is the lack of technological and labor resources available, which prevented the intensity of exploitation that would later be seen.

Prior to the rise of the Incan empire, the guano islands were ruled over by local ‘guano lords’ who utilized their position to achieve political power and wealth. By controlling the flow of guano, they controlled who had stellar harvests and who starved.

When the Incans came to power in this region, they removed the Guano lords and replaced them with a system where each village had a parcel on the Guano islands. During the mining season, they would be allowed to mine this specific parcel, allowing them to control access to this essential resource while also ensuring no one group accumulated too much influence over the islands. This wasn’t for altruistic reasons; however, this was instead a strategy to denude the power-base of local lords and establish their own systems of control over conquered populations.

The Columbian exchange

Eventually, the Incan empire would be supplanted by the Spanish (for a more complete story, I recommend this book). However, the colonists remained largely unaware of the immense wealth they had taken control of (though they would eventually try and reinstate influence over the trade in the Chincha War). It took Peruvian independence and the eyes of scientists for the ruling class to truly realize what they had. After a series of chemical experiments and agricultural trials, guano was shown to have immense value as a fertilizer (I guess the centuries of use among indigenous Andean peoples wasn’t enough evidence), and guano mined on Perus Chincha Islands was the purest in the world.

This led to a global boom, with Peru at the forefront. Having an international monopoly on this trade, money flowed into the struggling post-colonial state. They brought 12.7 million metric tons onto the world market. This ushered in what is known as the Guano era (what I am personally dubbing Pax Excrementa), a period of peace and prosperity. Massive investments were made in public works and the military. This wealth, however, mostly flowed to the already wealthy Lima elite and infrastructure to support the guano trade. Already desperately poor regions, like the Amazon, were left destitute.

Guano served as functionally the first globally traded fertilizer. It became critical to replenishing the fertility of Western Europe. England, in particular, purchased a large bulk of the world’s guano supply to grow feed for cattle, which in turn fed the growing consumer demand for meat. The sugar plantations of the new world were also major buyers of guano. This underscores how this scatological wealth was used to underwrite consumer markets as opposed to shoring up global supplies of grain during an era of intense famine. While the British middle class were enjoying their beef, the Great Famine of 1876–1878 likely killed 8.2 million people in their Indian colonies.

The wealth unleashed by the global guano trade enticed other nations to get in on the act and break the Peruvian monopoly. Searching for colonies with copious amounts of bird crap became an urgent matter for the empires of the world. This, of course, includes the American empire, which was in the middle of manifest destiny becoming the national ethos. Congress passed the Guano Islands Act, which allowed private citizens to claim unclaimed islands that may have guano on them for the United States. It also stipulated the military would back up these claims. This law is why the US has multiple tiny atolls and sandbars across the Pacific and Atlantic, including Jarvis Island (1.7 sq mi) and Kingman Reef (7 acre).

Pushing global agriculture

I’d like to return to a concept I touched on above. The idea that, prior to industrialization, we farmed in a manner that was far more ecologically grounded, and today we are divorced from the boundaries of our planet. The former period is known as the biological old regime, and the latter is the biological new regime. Under the old regime, resource and energy flows fed back to one another, with production and consumption being tied to one another in a circular relationship. Under the new regime, production and consumption are aggressively linear.

This is often framed as originating in and being driven by fossil fuel use, and while the ascendency of coal, oil, and natural gas supercharged this regime shift, its foundations are in the explosion of guano mining and export. It drove yields across the world in the 19th century, pushing farmers in North America and Europe squarely into the biological new regime. It was the exhaustion of the Chincha Island deposits and the overall decline of the industry by the end of the 1800s that led chemists around the world to search for other sources of nitrogen, including Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch.

An illustration of this process was how livestock and crops were pushed apart. Historically, most farms globally would include both in their operations, as the manure from livestock served an important role as fertilizer. While mechanization is part of the reason they are no longer needed on crop farms, the advent of affordable, quality guano fertilizer changed the calculus. It was now much easier to spread guano on ones field than to run cattle or chickens on it after harvest. With this connection severed, the forces of specialization took over, and people started focusing on crops or livestock and less on a system that included both. This has led us to today, where most farms are either crop farms or livestock farms, but almost never both.

I’ll let Cushman sum up the consequences this has had.

Rather than improving the world’s food supply during an era of profound environmental instability, Peruvian guano mainly served northern consumers of meat and sugar. Rather than inagurating an epoch of peace and prosperity, guano and nitrates inspired wars and fueled the growth of inequalities between clases and nations. Although guano and sewage disposal helped improve the soil and urban environmentss, nitrate mining deeply scarred the most ancient arid landscapes on earth. Most significantly, Peruvian guano opened the gateway to modern farming’s addiction to inputs.

I don’t want it to sound like we need to return to a medieval production system or standard of living. I believe a combination of technological innovation and social reform can deliver us to a circular future. In fact, my thesis work is, in a very small part, trying to figure out how to produce significant calories while reducing the need for such inputs. However, understanding the path that led us to this point is critical in ultimately leading us out of it. Guano is a foundational story of the development of modern industrialized agriculture.

I hope this has been an interesting and informative post. This was merely one part of the fascinating history of guano, which includes multiple wars, major shifts in culture, the development of states and empires, and the role of governments in managing natural resources. For a dive 100 times deeper than this, I cannot recommend enough Guano and the Opening of the Pacific Word by Gregory Cushman enough. I find explorations of the histories of specific industries or resources such as this to be fascinating, and I hope this was worth the read.

What I’m reading, watching, and listening too

Ol’ Man River - Really enjoying this cover of Ol’ Man River, one of the classic American songs of the Steamboat Era, by Kyle Taylor Parker.

A Smooth “Landing” for Sustainable Agriculture: Some intriguing thoughts from the AgPunk Newsletter about linkages between land access for young and marginalized farmers and sustainable farming.

How Your House Makes You Miserable: An interesting essay about how making homes our main store of wealth impacts our design choices (I don’t fully agree with every point, but it was thought-provoking nonetheless)