The political character of the prairie states today does not call to mind images of progressive action. Farm country in middle America is widely seen as the center for reactionary politics. Tax cuts, benefit curtailment, and deregulation, along with isolationism and cultural warfare, are the prime movers of prairie politics these days. It may come as some surprise that in the past, particularly between the Civil and Second World Wars, the Great Plains flourished with progressive political action. Solidarity and mutual aid ruled the day, and the enemies in the crosshairs were the banks and the railroads. Rural politics were defined by class struggle, not cultural warfare (not to discount the era’s rabid antisemitism). In this piece, I will tell three different stories of economic and political power building on the Great Plains from this era. I hope to capture the ideological character of the era and stimulate visions of a future prairie that we can aspire to today.

The 1932 Farmers Strike

After the conclusion of the First World War, rural America experienced a period of persistently low prices. During the war, production surged to feed the needs of soldiers for the US and its allies. After the war, fields overflowed with food, causing prices to drop. In response, farmers planted even more to try and get ahead of their mounting debts, stimulating persistent overproduction that depressed commodity markets and plunged farmers into a cycle of poverty.

Discontent spread through the countryside, fueled by resentment towards the railroads and banks that were seen as extracting what little wealth remained. Resistance movements sprang up, ranging from spontaneous outbreaks of violence to more organized opposition to the forces of the wealthy. Penny sales were a common sight in rural America, where a community would all show up for the auction of foreclosed farms. But instead of participating, the group was there to pressure off any serious buyers, keep the bids low, purchase the property for pennies, and return it to the family it was taken from (Seabrook, 2007).

Within this atmosphere sat Milo Reno, a veteran of rural organizing and leader within the Iowa Farmers Union, who put forward an audacious plan. Hold a national strike of farmers to show the nation that they are angry and powerful. Thus the Farmer Holiday Association was established.

Their theory of change was to “take a holiday” and withhold products from the marketplace. By ceasing the flow of meat, milk, and grain, the thinking went that commodity prices would rise due to the sudden demand. Additionally, organizers figured that this flexing of their collective power would force the government to the bargaining table and bring radical reform to the markets that have suppressed farmer fortunes for over a decade (Choate, 2002). The following poem, written by an anonymous striker, captures both their antipathy to the powers of industry and government and the strategy the farmers would use to bend them to their will:

Come fellow farmers, one and all –

We’ve fed the world throughout the years

And haven’t made out salt.

We’ve paid our taxes right and left

Without the least objection

We’ve paid them to the government

That gives us no protection.

Let’s call a “Farmers Holiday”

A Holiday let’s hold

We’ll eat our wheat and ham and eggs

And let them eat their gold.

- Anonymous poem published in Iowa Union Farmer, 1932

The focal point of the strike was in western Iowa where drought and a high foreclosure rate served as the impetus for organizing. Sioux City, where various supply chains converged, would bear much of their ire. Dairy farmers led the charge, as they were subject to the whims of but a few processors who exerted undue influence over prices, which fell from 40 to 19 cents in the five years before the strike (Shover, 1965). Farmers were able to halt the shipment of milk into the city and even distributed their product to residents free of charge, concentrating the impact of the action on commodity powerbrokers. Delivery of other commodities, such as pigs, was also greatly impacted by the strike. In the end, the Sioux City front was able to negotiate a major increase in the price paid to dairy farmers in the region, stabilizing the incomes of thousands of families.

While the center of the strike was set along the Loess hills of the Missouri River, Strike movements spread across the Midwest. A blockade of shipments into Omaha was launched in Council Bluffs, and across the state in Clinton a mob formed in an attempt to break picketers out of jail (Shover, 1965). Pickets and negotiation committees emerged in the Dakotas, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, centered around dairy and hog country.

While this was an incredible movement of solidarity, it did not by itself build sustained political power. Much of this came down to a lack of coordination between the frontlines and Holiday Association leadership. The latter took the view that the strike would serve as the muscle for negotiating legislative change and bring about a new commodity marketing system that put farmers in the driver’s seat (Shover, 1965). The farmers, who were carrying out the hard work of the strike, were using their newfound leverage to negotiate more immediate reprieves for their troubles, such as price improvements won in Sioux City. This coordination problem was largely borne out of strike leadership’s expectation that farmers would simply fall in line with the strategy they imposed upon them.

While the immediate demands of the strike failed to reach their immediate goals, their actions forged a long-term base of power. Both Roosevelt and Hoover, in the midst of the 1932 election, made promises to address the grievances of the strikers (Shover, 1965). Going into 1933, Reno attempted to relaunch the movement, but future strikes never materialized. The looming threat, and the attention to farmer’s plight that the 1932 action brought, compelled Washington to center agriculture in the coming New Deal (Choate, 2002). Soon, the Agricultural Adjustment Act would be passed, introducing price supports and production controls that brought a semblance of stability and safety to the Midwestern farm economy. Mollified, the farmers moved on to pursue more moderate forms of political action. Echoes of the striking movement, however, lived on into the 1980s, when during the Farm Crisis faint whispers of a new strike circulated once again across the Great Plains (Browne and Dinse, 1985).

Aaron Sapiro and the Mother of All Cooperatives

In the 1800s, agricultural cooperatives in the United States mostly amounted to locally owned grain elevators, shipping mutuals, and buying groups. Scrappy local institutions with little ability to move markets in the face of large national concerns. While they allowed farmers to scrape out a small bit of relief in the cutthroat economy, they by no means had enough power to force systemic change.

The one exception to this state of affairs was a couple of cooperatives established in California among orange and raisin growers. In contrast to their localized cousins, these cooperatives instead focused on organizing at the commodity level. By uniting the interests of all producers of a specific crop, the thinking went that more market power would be had, allowing them to collectively secure a better deal against railroads, grocers, and banks.

In came Harris Weinstock and Aaron Sapiro, agents of the California state government, looking to formalize and expand this model to other crops. Their core approach was farmers pooling the entire output of a crop into a single entity, democratically controlled and enforced through contracts (Ginder, 1993). This would win the farmers considerable market power with which they could demand fairer prices while also coordinating production to prevent oversupply.

While this model worked well in California due to the wide array of unique crops grown nowhere else in the country, coordinating cooperative marketing across a wider geography would prove challenging. Sapiro was a zealot for cooperative marketing, however, and evangelized the good word across the nation. His stirring speeches extolling the virtues of farmer collaboration drove the creation of numerous marketing associations across dozens of crops, including tobacco, potatoes, and apricots. At his height, Sapiro helped to organize 66 cooperatives that marketed $400 million of crops each year (Larsen and Erdman, 1962). But he was only getting started. His most ambitious project was just on the horizon.

To explore methods for reviving prices after the post-WW1 price drop, the nascent American Farm Bureau held a meeting in Chicago to discuss cooperative marketing. Sapiro was the headline speaker. His charisma won a loyal following and he joined the Bureau as Counsel (Truelsen, 2009, pp. 40–42). The eventual goal was to establish a national wheat and corn marketing cooperative – U.S. Grain Growers, Inc.

By coordinating national control of grain marketing, farmers would be able to sidestep the numerous middlemen that cannibalized profits from the business and reduce the influence of speculators. One legal hurdle remained, however. While recently anti-trust was meant to prevent big business from monopolizing different sectors, the way the laws were written called into question whether such cooperatives were even legal. The Bureau turned its new lobbying capacity to eventually get the Capper-Volstead Act passed, which would exempt such entities from the anti-trust (Truelsen, 2009, p. 38).

While the Bureau supported cooperative marketing in theory, the idea proved overly radical for some of the more pro-business segments of the organization. As a more conservative leadership took power in 1924 they fired Sapiro and quashed the grassroots pro-cooperative element, scuttling the effort and ending the dream of farmer control of the grain industry (Larsen and Erdman, 1962).

Eventually, several issues led to many of the state and regional-level cooperatives established by Spiro to collapse. The movement, galvanized by charismatic speeches by Spiro, never conducted the legwork to establish a sense of solidarity among members. They failed to cultivate the culture necessary to support the democratic governance of markets. Without this social buy-in, farmers didn’t feel a sense of purpose towards their cooperatives and distrusted leadership (Larsen and Erdman, 1962). Ultimately, Spiro’s speedrunning method of cooperative organization seems to have left the movement with a lack of a skeleton to hold it up.

The California cooperatives that inspired this whole movement are still going strong today in the forms of Sunkist and Sunmaid. The California model continues to inform cooperative marketing across crops. In 1972, the Central California Lettuce Producers Cooperative helped to stabilize winter lettuce prices (Lindsey, 1975) and the United Potato Growers have done the same for Idaho spuds, and they’re expanding to other states (Hardesty, 2008). It’s clear that, despite its initial stumbling blocks, the Sapiro model has the legs to improve the incomes and market position of farmers.

The Nonpartisan League and Public Enterprises

The same discontent that fueled the Farmer’s Holiday Association also drove a similar populist movement further west, this time centered in North Dakota. Private mills, railroads, and banks were seen as systematically shortchanging farmers, using their control over the flow of commodities and credit to extract prodigious amounts of cash from the working class. Out of this exploitative milieu rose a unique form of prairie socialism, which would manifest itself into the Nonpartisan League.

The League favored public ownership of critical agrarian infrastructure, promoting a platform that included public ownership of banks and grain elevators,1 state inspection of grain to ensure fair grading, and even an early form of disaster protection for crops2 (Levine, 1921). This focus on establishing public enterprises represented one of the first major surges of socialist public policy in the country, from the windswept interior of all places.

The League had a pragmatic and experimental approach to building power. They ran candidates under both Democratic and Republican tickets, depending on the local political landscape. If their preferred candidate lost, they would run them in the general election as a spoiler. In some states where their power base was small, they focused on using endorsements to pull more popular candidates to adopt their platform, and in states where they were more popular, they even launched third parties (Huntington, 1950). Their most popular third party, the Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party, was so successful it eventually merged with the state’s Democratic party, leading to decades of strong worker-centric politics in the state (Wright, 2022).

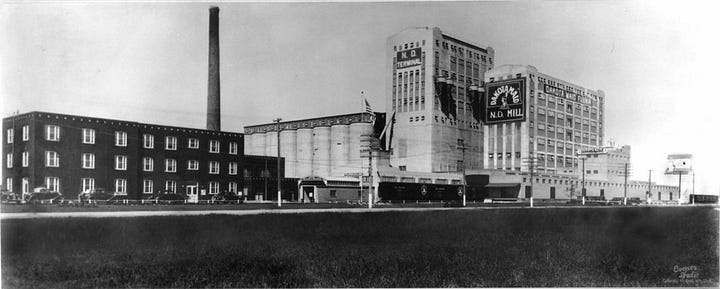

The League's home, however, was North Dakota, where their program of public enterprise proved most durable. Their two main successes were the establishment of the Bank of North Dakota and the North Dakota Mill and Elevator. The bank remains the only state-owned bank in the nation and provides low-interest loans on farm mortgages, allowing farmers to avoid the extortionate rates charged by Minneapolis banks (Wong, 2023). State government agencies were directed to utilize the institution for all deposits, keeping tax money circulating through the local economy.

Similarly, the State Mill was built to allow farmers to avoid the rail fares and low prices involved in selling their wheat in Minneapolis markets (Dykstra, 2012). The Mill was instructed to pay the highest price possible to farmers, forgoing any profit not required to maintain processing and storage facilities. The mill sold flour as well as pancake and bread mixes.

The League’s success in North Dakota launched a series of popular public ownership campaigns across the prairie. In the 1930s, Nebraska passed a series of laws that eventually resulted in all electric utilities in the state being community-owned (Hanna, 2015). The movement took a stronghold in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation, led by Tommy Douglas, founded a bevy of public corporations, including state-run power, water, and insurance services (de Bruin, and Lovick, 2013). This culminated with the establishment of Canada’s public healthcare system, which today provides free medical care for 40 million people.

The Nonpartisans League's pragmatic and experimental approach allowed it to trial out a series of political approaches and win political power across the upper Midwest. Had the movement attempted to establish a third political party, their efforts would have likely dissipated after one or two election cycles (Huntington, 1950). But what they lacked in numbers they made up for in strategy and thus were able to establish a coalition that crossed ideological and tribal divides and won enduring changes towards the public good.

Coda

Behind these three actions of economic solidarity and power building sits a rabid discontent with the business powerbrokers of the day. Railroads had a monopoly on the shipping of grain and meat which allowed them to charge exorbitant rates for moving commodities from field to market. Banks extracted large volumes of capital from rural areas, keeping farmers in poverty.

This is not dissimilar to the trends facing rural Americans today. Farmers are squeezed at both ends of supply and demand. Whether it’s buying tractors or selling beef, there are only a few firms to engage with, leaving large corporations with all the power and the farmers with none.3 This begs the question, why don’t we see a similar turn towards economic justice? Why are rural voters wasting their time on immigration or book bans?

In the 1970s, U.S. farm policy entered an era epitomized by the slogan ‘Get Big or Get Out.’ Consolidation wasn’t simply tolerated; it was expressly encouraged by Congress and the USDA. The impact of this policy is that farmers on the lower end of the economic totem pole were forced off the land when commodity prices crashed in the 1980s. Smallholders and tenants were the main victims of this shift, an income class that was more politically aligned with strikes, cooperatives, and the like. Meanwhile, the farmers who remained were larger landowners with deeper pocketbooks that were generally more economically conservative. Groups like the Farm Bureau, whose ideological development I recently profiled for Ambrook Research, fought against another strike and blocked a major debt relief plan that may have saved many smallholder farms if enacted. The long-term effect of Get Big or Get Out was the retention of wealthier farmers, pushing the ideological direction of rural America in a less radicle direction.

The subsidies paid to farmers are also probably a force preventing more radicle tactics from taking hold. The Farmers Holiday Association, for example, was in part mollified once New Deal programs were established that provided relief for farmers. While such programs may remove immediate economic pressures, they also remove the impetus for farmers to confront core structural issues against their economic success like oligopolies and land speculation.

Finally, demographics round out why I think rural America is less radical than in the past. Farmers and rural residents are much older than they were in the past, with the average age of farmers going from 49 in 1945 to 58 today. Older folks are more docile and less likely to partake in frontline political action, especially if they are only a few years from retirement. Stability is far more important to elders than the young, who have hotter blood and less to lose (or, more accurately, more time to earn it back).

This combination of ideological, demographic, and economic forces is, in my estimation, what has quelled the countryside from pursuing the prairie fire political organizing of yesteryear. Given the political tailwinds of today, resurrecting such a movement seems as far off as ever. But I hope these three stories can inspire political actors, both rural and urban, to devise strategies and forge visions of a more equitable and democratic future for the American Great Plains.

What I’m Reading, Watching, and Listening too

Live Near Friends: I recently stumbled upon this blog that provides great advice in navigating the logistical, legal, and emotional complications of getting dislocated friend groups to live closer to one another, or orchestrating shared housing arrangements. A great read in our modern era of lonliness.

References

Browne, W.P., and J. Dinse. 1985. The Emergence of the American Agriculture Movement, 1977—1979. Great Plains Quarterly 5(4): 221–235.

de Bruin, T., and L.D. Lovick. 2013. Tommy Douglas. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/tommy-douglas (accessed 27 March 2025).

Choate, J. 2002. Disputed ground : farm groups that opposed the New Deal Agricultural Program. Jefferson, N.C. : London : McFarland.

Dykstra, G. 2012. Pragmatism on the Prairie. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/31/opinion/pragmatism-on-the-prairie.html (accessed 27 March 2025).

Ginder, R.G. 1993. Aaron Sapiro’s Theory of Cooperatives: A Contemporary Assessment. Journal of Agricultural Cooperation 8: 93–102.

Hanna, T. 2015. Community-Owned Energy: How Nebraska Became the Only State to Bring Everyone Power From a Public Grid - YES! Magazine Solutions Journalism. YES! Magazine. https://www.yesmagazine.org/economy/2015/01/30/nebraskas-community-owned-energy (accessed 21 March 2025).

Hardesty, S. 2008. Enhancing Producer Returns: United Potato Growers of America. Giannini Foundation of Agricultural Economics.

Huntington, S. 1950. The Election Tactics of the Nonpartisan League on JSTOR. The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 36(4): 613–632.

Larsen, G.H., and H.E. Erdman. 1962. Aaron Sapiro: Genius of Farm Co-operative Promotion. The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 49(2): 242–268. doi: 10.2307/1888629.

Levine, L. 1921. What the Western Farmer is Fighting For. New York Times Magazine.

Lindsey, R. 1975. In California’s Lettuce Valley, a Harvest of Turmoil. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1975/05/10/archives/in-californias-lettuce-valley-a-harvest-of-turmoil-labor-and.html (accessed 27 March 2025).

Seabrook. 2007. Fending off Foreclosures with Penny Auctions. All Things Considered. https://www.npr.org/2007/12/09/17060380/fending-off-foreclosures-with-penny-auctions (accessed 27 March 2025).

Shover, J.L. 1965. The Farmers’ Holiday Association Strike, August 1932. Agricultural History 39(4): 196–203.

Truelsen, S. 2009. Forward Farm Bureau: Ninety Years History of The Americ…. American Farm Bureau Federation.

Wong. 2023. How fed up farmers started the only government-run bank in the US. Planet Money. https://www.npr.org/2023/08/23/1195518059/how-fed-up-farmers-started-the-only-government-run-bank-in-the-us (accessed 27 March 2025).

Wright, S. 2022. Farmer-Labor Party of Minnesota. EBSCO Research Starters. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/farmer-labor-party-minnesota (accessed 27 March 2025).

Facilities that store large amounts of grain, allowing farmers to have more autonomy in when to sell their product, giving them the ability to wait for good prices to come in after the immediate harvest is complete.

In the form of hail insurance

At least in terms of market power