The Myth of the Corporate Farm

In discussions about American agriculture, a dichotomy has emerged defining the contours of the conversation. The family farm vs. the corporate farm. The former are idolized as stewards of the land, pillars of the community doing the hard work of feeding the nation with an independent attitude and a little elbow grease. On the other side is the corporate farm, who are blamed as the primary source of pollution, labor abuses, and economic strife. Calls for regulation and reform mostly target these entities, with the idea that if we let family farms flourish our rural lands, waters, and communities will finally heal.

Unfortunately, “corporate farms” are almost non-existent in rural America. Nearly all farmland in the U.S. is owned or controlled by family farmers, as I will show below.

A breakdown of farmland ownership

Most family farms in the U.S. are organized as LLCs or Corporations, so looking purely at the quantity of land owned by corporations may give the appearance of vast corporate control of America’s farmland, even if most of those corporations are “Bob Smith Family, Inc.” type entities. To get a clearer picture of the situation on the ground, we need to look at the USDA Economic Research Service’s Tenure, Ownership, and Transition of Agricultural Land Survey (USDA-ERS, 2024).1

61% of America’s farmland is directly owned by the farmer who farms the land, the archetypal ‘family farmer.’ Small family farms are more likely to control the land they farm, with larger (still family-run) operations consisting of a mix of wholly owned and rented land. Additionally only four percent of owner-operated farmland is owned by a non-family farm. 96% of non-rented farm and ranchland in the country is owned by a family member with a direct connection to the land and community that relies upon it.

The remaining 39% of farmland in this country is available for rent. 38% of farm landlords are retired farmers and another 20% of landlords are active farmers renting out a portion of their land, normally in preparation for upcoming retirement. The last portion of farm landlords are those who have never farmed directly. Most of these individuals acquired their land through inheritance (mainly children and widows of farmers). Adding these numbers up, a minuscule quantity of rentable farmland is left to be owned by distant corporate interests. At most, this represents 10% of American farmland. However, a good portion of this 10% are family trusts and similar entities of individuals who were close to the farmer that initially owned the land. All in all, a truly tiny portion of American farmland is in the investment portfolios of integrated food companies, billionaires, and investment firms.

Even with this miniscule ownership rate, these firms aren’t causing the destructive farming practices on the land they own, at least not directly. Corporations and private funds invest in farmland for passive income, as a hedge against the volatility of the stock market. It’s a safe place to park money while generating rental income. They don’t care about micromanaging what their renters do with the land. At most, rental contracts will include a duty to control noxious weeds (National Agricultural Law Center, n.d.) and there appears to be little difference in conservation practices associated with rental vs. owned land (Burnett et al., 2024). Due to their passive nature and tiny land holdings, the destructive practices employed American agriculture plainly cannot be associated with corporate ownership of farms. However, they do drive harmful practices in the other ways corporate America weildpower over farmers.

The structure of power in the food system

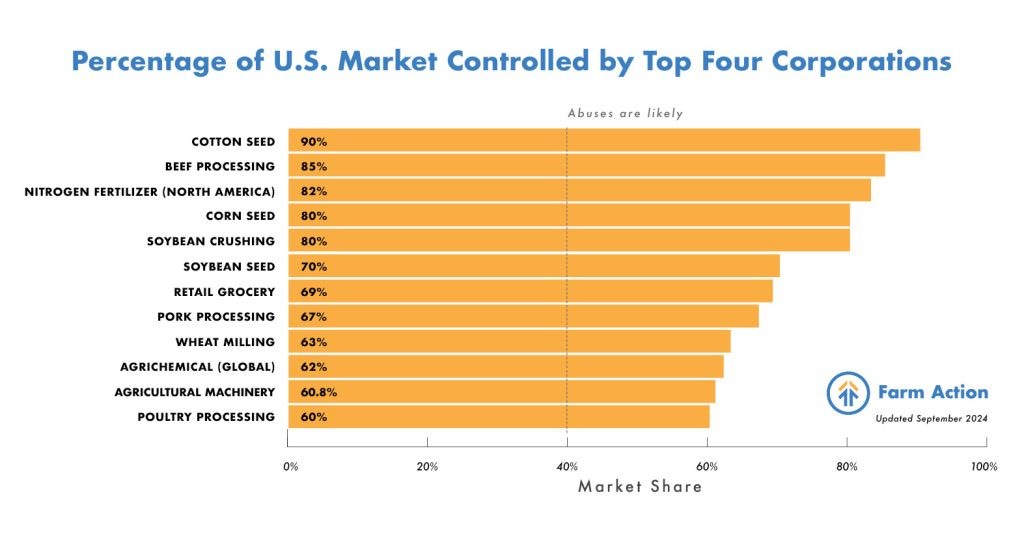

Despite the lack of appreciable corporate ownership over land, corporations exert a lot of influence over the food system, just along different lines. This power comes in the form of control over supply chains. A small number of corporations control the seed, input, and machinery markets, allowing them to push prices higher for farmers (Farm Action, 2024). Similarly, only a few companies buy the majority of grains, fruits, vegetables, meats, and dairy products, allowing them to push prices lower and transfer as many costs as possible onto farmers (Howard, 2021). Look at contract animal feeding for an example. Poultry firms like Tysons own the birds, but farmers own and maintain the facilities and purchase the feed. This structure allows the firm to own everything that makes money and forces farmers to own everything that costs money (Nargi, 2017). The production model is designed by the demands of the supply chains, of those purchasing the commodity the farmers sell. A combination of contract stipulations and rock bottom prices make it more difficult for farmers to invest in sustainable practices. Arrangements like these are what allow corporations to control the food system. The myth of coporate land ownership conceals the methods by which corporations exert power over the food system and fails to accurately analyze how family farms integrate into supply chains.

This acts to protect corporate power by clouding our judgment and pursuing ineffective strategies in confronting it. Instead of breaking up these massive companies and creating markets with more competition that are fairer to farmers, we waste our time on land ownership restrictions that do nothing to disrupt the status quo, since that’s not the base on which power in the food system is built.

This obfuscation also shifts the moral burden of the problems of agricultural production away from actual decision-makers and onto a nebulous enemy. This arrangement tacitly absolves family farms of issues of environmental degradation, labor abuses, and wealth accumulation (Hoffelmeyer et al., 2024). Ownership structure is not deterministic of agricultural practice. The romanticization of family farming, however, shrouds their influence and complicity in the existing industrial food system, which is much more nuanced than a simple ‘little guy vs. corporate elite’ narrative. While there are many ways in which corporations influence such decisions, the exact causes of outcomes are multifaceted, and focusing on this simple story obscures the best route toward reform.

Family farms need to be held to account for their environmental and social records. Many of them are members of local political and economic elites and hold substantial volumes of capital and resources. They make management decisions that are in direct opposition to environmental quality and economic justice. At the same time, corporations design contracts and markets to extract as much wealth from rural America as possible. Family farms are highly tied into the corporate food system in complex and multifasceted ways. The material reality of these relationships between players should be what informs how we pursue reform, of both corporations and family farms. Placing the responsibility for these misdeeds on nonexistent corporate farms only serves to perpetuate the industrial food system and prevent its dismantlement.

What I’m Reading, Watching, and Listening too

The Enchanting Visuals of Portuguese Fish Tins: Like many, I’ve fallen down the tinned fish rabbit hole. And who can blame me? Just look at these beautiful designs.

What if England Never Became French?: Who doesn’t enjoy some alternate history?

The Christian Publishing Industry Failed Women: A moving personal essay about how the themes prevalent in Christian writing for women have impacted the author.

References

Burnett, J. W., Szmurlo, D., & Callahan, S. (2024). Farmland Rental and Conservation Practice Adoption (No. 270; Economic Information Bulletin). USDA Economic Research Service. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.341821

Farm Action. (2024, July 24). Agriculture Concentration Data. https://farmaction.us/concentrationdata/

Hoffelmeyer, M., Sexsmith, K., & Glenna, L. (2024). Divergent approaches to the ‘family farm’: Celebrate, reform, or abolish? Agriculture and Human Values. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-024-10628-6

Howard, P. H. (2021). Concentration and power in the food system: Who controls what we eat? (Revised edition). Bloomsbury Academic.

Nargi, L. (2017, March 10). The Continuing Woes of Contract Chicken Farmers. Civil Eats. https://civileats.com/2017/03/10/the-continuing-woes-of-contract-chicken-farmers/

National Agricultural Law Center. (n.d.). Agricultural Leases Overview. Retrieved December 19, 2024, from https://nationalaglawcenter.org/overview/agleases/

USDA-ERS. (2024). USDA ERS - Farmland Ownership and Tenure. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/land-use-land-value-tenure/farmland-ownership-and-tenure/

Since this survey was conducted in 2014 a moderate amount of land included has been sold to another party. However, it should be noted 25% of land transfer has been to to someone unrelated to the seller. This indicates that the situation is relatively similar to that a decade ago.