In the mountains of Northern Spain, in the culturally distinct region known as the Basque Country, lies the world's most successful cooperative. Mondragón, today a federation of 110 cooperatives and over 80,000 employees, started as a technical college in its eponymous town founded by José María Arizmendiarrieta, a catholic priest who sought to build the social and economic capital of the economically depressed community. In addition to practical skills, he also taught values related to Catholic social thought, such as solidarity and collaboration, along with sociology. Combined, these laid the foundation for the eventual cooperative movement.

The first cooperative that would eventually evolve into the Mondragón Federation was Ulgor, a workshop that manufactured appliances for home use. Over time, new enterprises were formed from Ulgor, including one that made tools, one that made valves, thermostats, and similar components, and one that took over a metal foundry. Ulgor was the initial customer of all these enterprises, which were established to replace privately owned suppliers that serviced Ulgor but were in time spun off as independent firms. This basic pattern of nursing new firms off as contractors of established cooperatives is how most of the complex’s members were created.

Mondragón is often cited by the New Economy Movement as a proof of concept that economic democracy can thrive. However, that’s often where the analysis ends. It’s worth digging deeper to understand the strategies that brought the complex success and to analyze the conflicts and missteps along the way. Only then can we understand how they built such a strong organization, and what to take away from their history.

Building a complex

One of the greatest strengths of the Mondragón federation, a strategy that helped it grow to the heights it did, was to create an ecosystem of cooperatives founded on the strength of their predecessors. The organization strives towards cooperatives of moderate size to maintain a communitarian work culture and to prevent the formation of a bureaucratic elite within firms. Once a cooperative becomes too large, specific product lines or business activities are cleaved off into new enterprises. Additionally, if there is a component that a cooperative purchases from a private firm, such as thermometers for refrigerators, the complex will try to organize a cooperative built around that activity and switch to procuring through the new firm. In this case, as much revenue as possible continues to circulate through the cooperative movement, instead of it flowing back into the private market. Over time, this has led to a large network of cooperative production and service firms that buy from one another, strengthening their common cause and the movement for worker democracy in the region.

In addition to this continual incubation of new cooperatives, the complex has established several “supporting organizations” that member firms share to provide critical services and social infrastructure. The Caja is a bank that organizes loans for new cooperatives, extends credit to existing firms, and offers an array of other financial services for both firms and their employees. Additionally, the complex established a mutual benefits organization that provides health and unemployment insurance as well as retirement pensions. Finally, a research group staffed by engineers and scientists provides manufacturing and economic research and development services. By sharing these institutions, each group can share costs and have access to services that are only otherwise available to large corporations.

This structure also allows the federation to establish mechanisms of mutual accountability among member firms. A common process among cooperatives is the slow creep into becoming a private company whereby the founding members expand the enterprise by recruiting nonmembers who don’t have a right of a governance vote or share of profits. This allows founding members to maintain a larger share of profits but eventually dilutes the firm into a traditional corporation. While the complex has a rule that no more than 10% of a cooperative can be staffed by non-members, all it takes is a single vote to undo that rule in an individual firm’s bylaws. Thus, to keep each enterprise in compliance with the cooperative mission, maintaining a dedication to a set of principles and rules is a condition for membership in the Caja. Each cooperative is reliant on preserving worker democracy to maintain access to credit and banking services. This and other forms of solidarity and mutual support keep the overarching mission alive.

This model also helps the complex deal with the problem of slowing employment. When one firm experiences slowing sales or other challenges that reduce its financial strength, excess labor can transfer to another cooperative that is growing. This also makes federation members more resilient to shocks, such as when Spain entered the European Common Market and was suddenly exposed to intense competition. Excess staff in the older industrial firms were able to transfer to newer service and agricultural firms. This also has the potential to make weathering the shocks of automation easier for workers, since there’s a built-in retraining and replacement system that allows for improving productivity without displacing workers.

The union question

One drama in the history of Mondragón was a strike that occurred in 1974. Months before, the governing council established a complex-wide worker evaluation program, meant to standardize job placements and promotions based on individual performance. While there would be no change in immediate pay, there were grievances among workers who were reassigned. They were concerned about their ability to attain more desirable positions in the future and the general loss of prestige with their downgrading. While this move was done to make the constituent firms nimbler and more effective, it struck many workers as antithetical to the principles of an egalitarian workplace. Calls for a strike began to circulate.

Management attempted to head this movement off by reiterating promises of pay security and emphasizing the transparency of the democratically elected governing council in designing and implementing the system. Nevertheless, in June an informal committee of workers at a refrigerator plant approached their managing team with a demand to immediately halt the review. The governing council rejected the demands, asking the agitators to follow the defined grievance process and appeal to their social councils (essentially committees interfacing between workers, management, and the governing council).

The strike lasted several days, with the governing councils refusing to heed the demands. Many of the workers, loyal to the cooperative, persuaded the strikers to leave the factories, moving from a sit-down strike to an outside picket. The governing council moved to expel any strikers from membership, which coaxed all but 17 strike leaders to return to work. These individuals were then expelled (though most would eventually be readmitted).

I find this a complicated story. On the one hand, no matter how democratic, any cooperative of a reasonable scale will bifurcate into managers and workers. As long as worker power over managers is preserved and communication and socialization are maintained between the two groups, democratic decision-making can be realized with such bifurcation. However, if either of these conditions are not met, it's beneficial to have a mechanism to reestablish worker control. Unions are a well-positioned model for this role. In the context of a cooperative, however, when there is structural equality and accountability between members of a firm, unions have the potential to become a special interest group. By coordinating an electoral minority into an organized power block, they can wreak havoc on operations. In the hands of workers vs. a powerful owner, such power brings about higher wages and greater benefits. In the hands of workers vs. workers, all it does is hold the organization hostage to avoid the will of the majority.

Democracy requires dissent, and dissent demands that some parties lose at least some of the time. In a cooperative setting, unionization becomes a tool of the dissenters to undermine the rule of democracy. A union can be a great way of maintaining the integrity of a cooperative, but it can also be used to subvert that integrity. Whether that’s a risk worth taking, I do not know.

The seduction of privatization

A common pattern that befalls worker cooperatives is a slow backsliding away from a truly democratic institution into a facsimile of a private company. For an example of this facsimile, look at the American grocery chain Hy-Vee, which purports to be employee-owned, gesturing at some sort of cooperative model. In actuality, the chain is owned primarily by executives and store managers, who have voting rights over corporate governance decisions. Front-line employees, such as cashiers, stock people, and departmental clerks, may only acquire ownership by investing their own money into the company’s 401(k) plan, which doesn’t include any voting rights.

Other cooperatives, such as the Pacific Northwest’s plywood coops, have expanded not by increasing their membership, but by hiring nonmembers as regular employees to increase the ownership value of the founding membership. This leads to the dilution of the cooperative with the original members slowly becoming traditional owners in what becomes a private company. As this foundational membership retires, with few existing workers maintaining an ownership stake in the firm, the only course of action is to sell the formerly democratic workplace to a private corporation, as nonmember workers rarely have the capital to purchase an entire firm and reestablish democratic rule.

Mondragón has been able to avoid this fate, but not without conflict and compromise. One decision the cooperative made early on was to establish a ratio tying the maximum pay with minimum pay. The initial rule established that the highest-paid employee of the firm could not pay more than 3 times what the lowest-paid employee made. This helped to ensure that a class system among members did not emerge, to build in a mechanism for the lower-skilled workers to see healthy wage increases as firms modernize, and to recognize a sense of egalitarianism among workers regardless of skillset.

Over time, however, this rule proved limiting to the organization’s expansion. They found a large volume of executives and managers leaving for the private sector, attracted by the higher wages traditional companies could pay1. The pay ratio rule prevented lots of talent from staying with the organization, which proved a long-term risk as the complex grew, requiring highly competent executives and technical staff. Thus, to compete with the wages in the marketplace, the ratio was expanded to 4.5 to 1 and again to 6 to 1. Of course, that’s still incredibly egalitarian compared to the 298 to 1 ratio at Inditex, Spain’s largest company, or the 1,188 and 1,224 to 1 ratios employed at Walmart and McDonald’s, respectively.

I go back and forth on this decision. On the one hand, having a tight wage ratio is something I strongly believe in ideologically. I do support a modestly higher pay for those with a high skillset or for those taking on the stress and time burden of leadership. As an executive, you should always be on call, able to dedicate whatever needs to be done to ensure the success of a firm. I find a wage premium reasonable for such positions (as long as they are the first to receive cuts in times of hardship). However, once such a ratio gets particularly high, it creates a cultural rift between different levels of an organization, particularly when such a rift also tracks with the managerial hierarchy. That flies in the face of the principles of economic democracy.

On the other hand, in this situation, attracting such talent is essential for a firm competing in the marketplace. And if private firms are willing and able to pay top dollar for talent, it’s a matter of survival for a cooperative to be able to match those salaries. And maintaining such a ratio would often lead to financial ruin for a firm. So, the choice does have a pragmatic logic to it.

Ultimately, this contradiction between principles and practice is a perfect demonstration of the difficulty in establishing and managing a doctrinally consistent cooperative in an autocratic market economy. In a fundamentally unequal society, it's impossible to establish an island of equality without some manner of erosion.

Conclusions

While this post paints a picture of strategy and persistence being the main factors for Mondragón’s success, other factors helped lead it to prosperity. Much of its growth occurred during a boom in the Spanish economy in the 1960s, which helped propel the complex in its early days as there was a lot of available demand in the marketplace. Additionally, the founders got incredibly lucky in being able to purchase an unused business license from a failed company and convince the Franco government to recognize the cooperative's establishment. However, successfully establishing economic democracy and expanding it into dozens of enterprises is still an incredible accomplishment, no matter how lucky the founders. The structure of the federation, with its mechanisms of inter-cooperative flows of wealth and resources, helps to institutionalize solidarity, stability, and equality, propelling the federation to incredible heights.

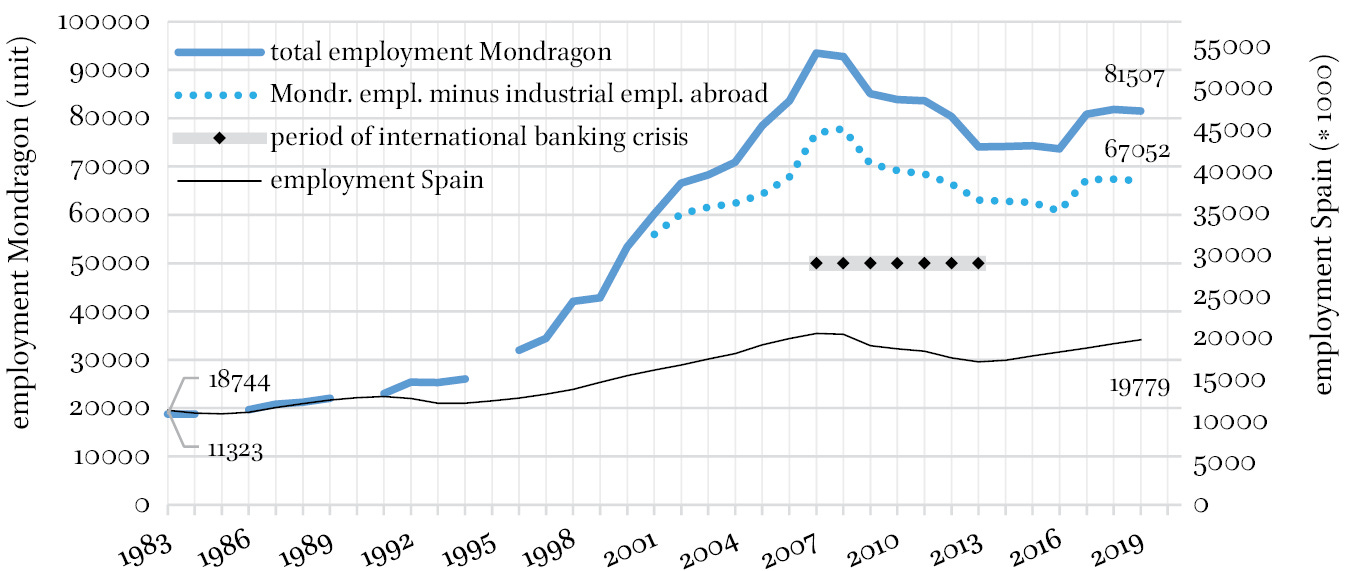

Most of the information in this post came from a book published in 1991 (discussed further below) and the analysis is based on the period between the 1960s and the 1980s. While I cannot speak to the details of the cooperative's institutional and social success since the 1990s, based on employment figures since the book's publication it seems Mondragón is still quite successful. While its employment rates have slumped since the 2008 financial crisis, and several prominent firms have either left or gone bankrupt (such as Ulgor), Mondragón maintains itself as a strong example of the power of the cooperative.

The stories and information detailed in this post come from the book Making Mondragón: The Growth and Dynamics of the Worker Cooperative Complex by William and Kathleen White. I consider it essential reading for anyone interested in economic democracy. It goes deep into the minutiae of institutional design, strategies, and management decisions. While much of what I focused on is the later institutional aspects of Mondragón, the book also details many of the earlier decisions when the cooperative was smaller, giving insight to those planning on establishing a cooperative enterprise. It’s an excellent peak into the organization's successes and challenges and has many more lessons for those seeking to advance the cooperative movement.

What I’m Reading, Watching, and Listening to

If You Ever Stacked Cups In Gym Class, Blame My Dad: Of course the guy who popularized cup stacking was a clown turned gym teacher.

Some Viking Warriors Were Probably Men: Some poignant historical satire.

I reviewed every snack in our office kitchen: An amusing reprieve for the office weary.

Though, it was found that executives who grew up in the training and social opportunities provided by Mondragón had a much lower attrition rate than those who were brought in already established in their careers, showing the strong social bonds and idealism membership in a cooperative engenders. So much so that even the seductive pay of a private corporation could not draw away executives who were dedicated to the community.

I find corporate governance structure interesting. I'm not super ideological, but I do tend to agree that firms could have decision making made in a more decentralized way the majority of the time. I think not being tied to things like having direct democracy might be useful. The goal, at the end of the day, is to align incentive structures so that workers will is taken into account and they aren't screwed over. Some people would want direct democracy and it may sound good, but I don't think it would work in a 40,000 person organization.

I think paying the managerial group more is fine to some degree as long as there are checks on their power. You could have something like a worker Republic where the workers elect their representatives to manage them and could have recall elections or vote them out. The worker's could have ballot initiatives based on signatures to have a way for bottom up policies to be implemented. The worker's could also have a veto mechanism for preventing bad or unjust managerial decisions from being implememted.

Basically, any policy or mechanism which has been applied in political democracy should be considered in constructing economic democracy. There are a wealth of best practices and case studies to examine so that you can best structure your organization and avoid pitfalls associated with consensus decision making.

Really excellent, concise, easy to read, in-depth discussion of the benefits and internal challenges the Mondragon Cooperatives have faced. Suggest you send this to Communities Magazine too. It has more depth and is not a puff piece.