Seeds of Prosperity: The Green Revolution

Before I get into this post, I wanted to plug an article I wrote for the Iowa Capital Dispatch, a nonprofit newsroom covering politics and policy in the state. It’s a deep dive into how demographics and history coalesced to inflate the costs of maintaining roads in rural areas. Enjoy!

I’ve decided to launch a new series on this blog called Seeds of Prosperity. For some background, one of my undergraduate majors focused on agricultural development and food security and how social, political, and economic systems interact with natural and agricultural resources. Before my master’s, I worked on several projects oriented towards agricultural development, focused on seed systems, crop stress in developing countries, and fair trade in tropical fruit. And since my current position is focused more on direct biophysical research, I’d like to have an avenue to explore some of the topics I touched on more in my past life.

This series aims to dive into different agricultural, rural, and international development programs worldwide. There are so many fascinating case studies, both successes and failures that can teach us a lot about how to better improve the lives of the world’s poor, hungry, and disenfranchised. By dissecting the approach and results of different development programs, I hope to enhance my and my audience’s understanding of economic and social development. And now, for my first post, lets dive into one of the most significant and controversial programs of agricultural development — The Green Revolution.

The Productivist Perspective

There are two common narratives detailing the conceit and impact of the Green Revolution. The first one I will tell is the productivist narrative.

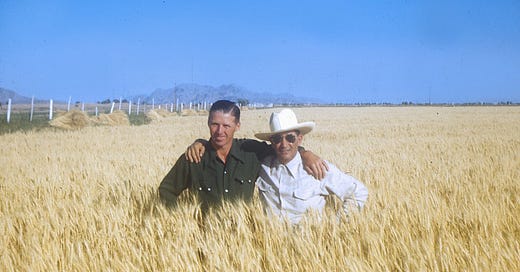

Our story begins in Mexico with the Rockefeller Foundation’s Mexican Agriculture Program. The ostensive goal of this effort was to improve the productivity of crops in Mexico to boost economic development and make the country self-sufficient in grain. Still economically slumped from the Great Depression and isolated during the Second World War, Mexico was flirting with famine as food production slackened. Boosting producitivty and establishing self-reliance was a central goal of the Foundation. And one of the scientists recruited to this effort was a young Iowan — Norman Borlaug.

Originally a forest pathologist, Norm was hired to help combat wheat rust, a fungal disease that infects wheat stems, causing the heads to become brittle and not fill out with grain. It can be devastating to wheat yields, and outbreaks are major causes of famine. Norms’ central innovation was a strategy called wide adaptation. Plant breeding in those days was heavily regional; breeders produced cultivars in the region where they were intended to grow. Growing a wheat variety from Texas in Nebraska was unheard of. Norm, determined to have as many chances to develop rust resistance, petitioned to have two breeding sites: one in the hills surrounding Mexico City and the other on the coast in Sonora. The former’s wheat season was much earlier than the latter, allowing multiple opportunities to find a cross that could resist the onslaught of stem rust.

In shuttling his seed back and forth between these two locations, Borlaug was also imbuing his wheat with the traits necessary to survive in a host of different environments. Instead of being optimized to a specific region, his wheat could survive a plethora of different light and climactic conditions. This light trait proved critical, as most wheat at the time was photo-sensitive, meaning it needed a certain quantity of light before it would flower. Wheat varieties were adapted to the light conditions in their region, so wheat from Italy would flower according to Italian light conditions. In contrast, wheat in England was only adapted to English light conditions. By developing photo-insensitive wheat, as long as the plant received adequate water and nutrients it would flower at a set time regardless of light exposure. As this wheat spread around Mexico and other nations came calling, this flexibility in the growing environment would prove critical to the success of the Green Revolution.

By the end of the breeding program, Borlaug developed wheat that was rust-resistant, high-yielding, geographically adaptable, and made quality bread. However, there was one final hurdle. The long-stemmed wheat coming out of the Rockefeller program was so top-heavy that it began to bend over, or lodge in the parlance of agronomists. This could compromise the entire endeavor, as wheat toppled to the soil before harvest was useless as food. Thankfully, at this point, Borlaug got his hands on a Japanese wheat variety called Norin 10, which was a dwarf wheat. By integrating this trait into his existing stock, Norm solved the lodging problem, and his high-performing, rust-free, globetrotting wheat was ready for the field.

As Mexican agriculture blossomed, other nations began seeking the advice of the Rockefeller Foundation and Borlaug on how to advance their own production. A large portion of this interest came from the Indian subcontinent, scarred by a colonial legacy that neglected their food production in favor of cash crops coupled with a large and growing population. Pakistan and Bangladesh were major players, but India was especially interested. India relied on food assistance from the US (1/5th of American production), which used it as a leash to control policy in the nation.1 Achieving caloric self-sufficiency was a paramount policy for Indian politicians.

Borlaug’s seed began showing up in test plots in India, and its success caused Indian agricultural researchers, namely M.S. Swaminathan, to send for Borlaug and Rockefeller support. Large volumes of seed were brought into the country and distributed to farmers and the yield breakthroughs seen in Mexico again came true. It wasn’t just plant breeding; the expansion of access to irrigation and fertilizer and access to subsidies made the Green Revolution model successful in India, Pakistan, and the Philippines.

By now, a model of high-yielding varieties, developed via wide adaptation and carried through by improved irrigation, chemical inputs, machinery, credit and subsidies, and infrastructure transformed agriculture in Asia and Latin America. Nations that formerly teetered on the edge of famine were feeding themselves and developing export markets for their surpluses. Additionally, new crops were being added to the mix, such as corn and rice.

In numbers, the Green Revolution was a major improvement. Total food production in developing nations doubled during this period, with Chile showing the starkest increase in grain production recorded in history.2 Another core success of the Green Revolution was its ‘land-sparing’ effects. Food production increased with little to no increase in land used for agriculture, allowing us to fight hunger without transitioning wilderness into cropland. Food production in Asia doubled while only increasing its land footprint by 4%3 and saving a land area the size of Kentucky and 2 million hectares of forest from conversion into cropland.4

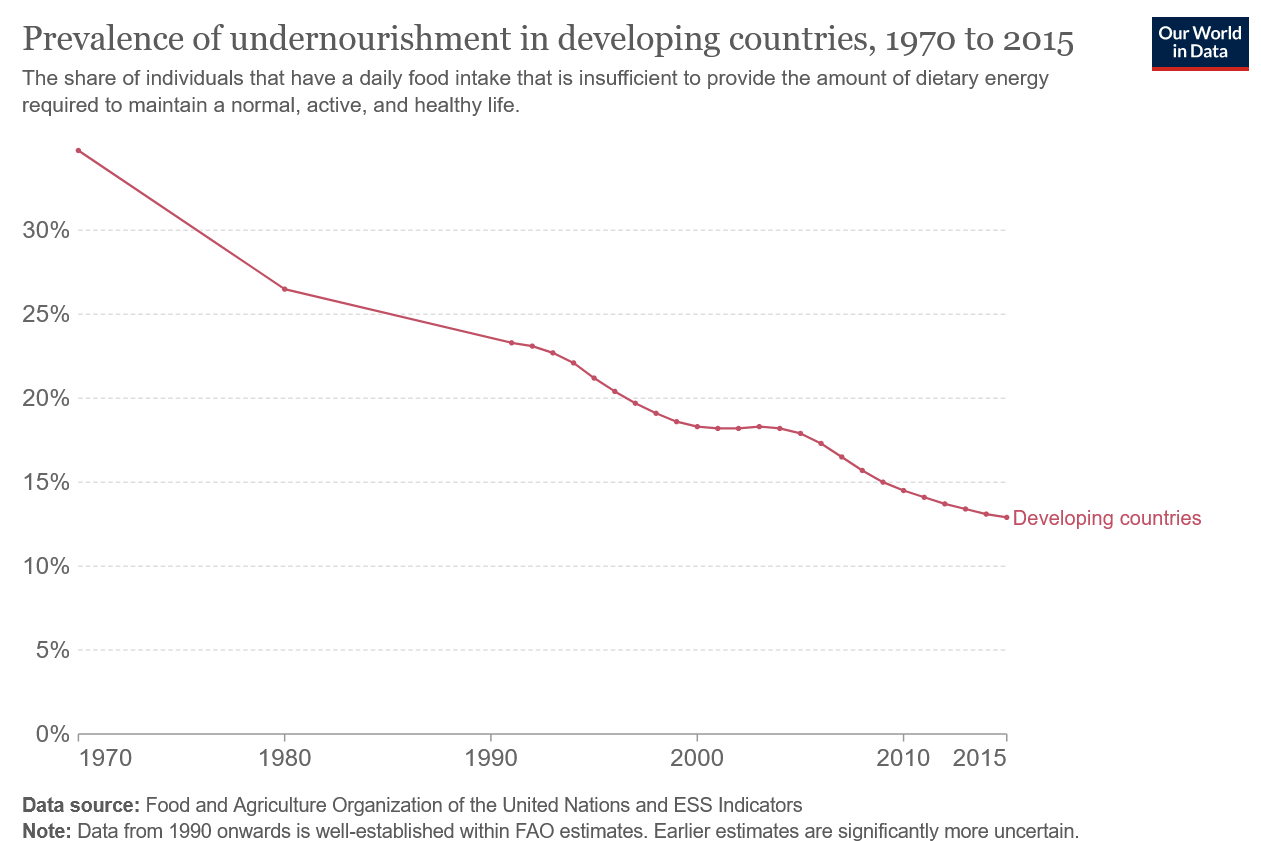

Of course, production is not the most important indicator in agricultural development; hunger is. While this aspect of the Green Revolution’s legacy is much more checkered overall, it seems that malnutrition rates went down substantially during the period after the Green Revolution. While data from the period during the Green Revolution is much more scattershot, this seems to imply that the technological adoption drove improvements in broad food security.

This can be seen readily in infant mortality rates estimated to have dropped by up to 5 points in areas where the Green Revolution occurred, translating to 3-6 million infants saved.5 This success was most impactful among poor families and male infants.

The myriad successes described above have led to calls for a ‘Green Revolution 2.0.’ Much of this rhetoric focuses on Africa, famously left over during the first Green Revolution due to African governments' lack of financial capacity and a general focus among first-worlders towards Asia and Latin America. This has led to the establishment of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (disclosure: I was briefly employed by a grant funded by AGRA). Many leading agricultural research and development organizations, such as the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center and the International Rice Research Institute, were founded to carry on the Green Revolution and continue advocating for the Borlaug package to solve global hunger.

The Socio-Ecological Perspective

The Productivist perspective is, of course, only one side of the story. The Green Revolution is controversial for a reason, and those criticisms mainly center on the social and ecological legacy of the incredible technological shift that occurred because of Borlaug’s innovations.

A central critique of the Green Revolution centers on the innovative wide adaptation approach Borlaug came across in Mexico. The phrase wide adaptation can be a bit misleading, as it implies it can perform well in every environment. While this is true from a light and altitude perspective, it is not entirely true from a water or nutrient perspective. Borlaug’s wheat needed a baseline amount of water and fertilizer inputs, and it was fairly high in these requirements. So in areas where this baseline couldn’t be met naturally, resources needed to be brought in to support the wheat.6 While this was broadly profitable and productive, it was not an accessible strategy to every farmer, leading to a lopsided adoption of the innovative wheat in favor of those who could afford fertilizer and irrigation.

The spread of Borlaug’s varieties also led to the loss of a ton of locally adapted seed used for millennia and the reduction in dietary diversity and access to traditional foods in favor of cheap and productive wheat.7 While that seed was not particularly productive, it was less input-intensive, meaning it could be raised by smallholder farmers independently. Local varieties were also more environmentally resilient and generally better weathered stress, such as drought. The simplification and streamlining of agricultural production generally pushed out the poorest farmers off the land, led to production consolidation, and reduced system resilience. While some of these now landless folks could be absorbed by the labor market in sectors like manufacturing, in more economically distressed regions they were left to languish.

Another major criticism of the Green Revolution was its failure to equitably distribute the gains in yield among the worlds hungry. While the rates of starvation and malnutrition went down during the period in target countries, they could have gone lower if distribution had been better. This echos one of the major failures of modern agricultural policy, where we have enough food to feed everyone but fail to deliver said food to hungry mouths. Many Green Revolution nations directed a portion of their yield gains not to hungry mouths but to economic development efforts. Mexico, for example, put wheat towards beer production8 and sorghum to livestock,9 neither of which meaningfully fed still sizable populations of hungry people.

The kind of hunger that was addressed also failed a number of individuals. The crops Borlaug and his intellectual descendants focused on were cereals — wheat, corn, rice, etc. These are all carbohydrate crops, and while carbohydrates are central to a nutritious diet, they do not fulfill every need. Focusing on cereals is a great approach if the issue is mere calorie deficiency. However, another form of hunger stalked the land and continues to impact hundreds of millions of people. So-called hidden hunger, as one can appear well-fed, is micronutrient deficiencies. A lack of vitamins and minerals in diets contributes massively to malnutrition globally. The types of crops that fix nutrient deficiencies are generally horticultural crops — fruits and vegetables. Another major type of malnutrition, protein deficiency, is best solved by improved availability of bean, lentil, and nut crops. Ignoring these crops in a fight to solve hunger was a major shortfall of the Green Revolution and one hunger fighters today are desperately trying to correct.

A final set of issues with the Green Revolution focus on its ecological impacts. The high-yielding varieties Borlaug ushered into the world required a massive scaling up of inputs, including fertilizer, pesticides, and machinery.10 Fertilizer use leads to a major disruption in local ecosystems as nutrient balances are thrown off and take a lot of fossil fuels to produce. Pesticides are harmful to local wildlife and are incredibly damaging to worker health. Finally, machinery use can negatively impact soil through compaction, increase the intensity land is used, and emit a lot of carbon from fuel use.

While the land spared by the Green Revolution is absolutely an environmental win, the harder use of existing cropland has steamrolled several more ecologically balanced cropping systems and replaced them with cropping systems that are input-intensive and much more simplified and intense. Instead of rotating a cereal, legume, and livestock over a three-year period, letting the land rest and restore its fertility, the land is ridden as hard as possible to squeeze out as many calories as possible. This is only sustainable for so long, and the erosion and degradation associated with intensive monocultures compromise the future productivity of those lands. Additionally, the biodiversity of pre-Green Revolution cropping systems, the thousands of local varieties of vegetables, grains, and legumes, has been lost to the same couple of varieties of wheat, corn, and rice. This ecological simplification of our cropping systems makes them much more vulnerable and dependent on inputs.

Pasts and Futures

I believe there are merits to and valuable lessons in both of these stories.

Many critics of the GR note that a continued focus on production over all is not a winning strategy in the 21st century. They rightly point out that we currently have enough food to feed the planet's population; the true barrier to food security is a lack of access to this bountiful harvest among the world’s poor. That hunger is a choice that we are making. This fails to consider that the only reason we have a choice in the first place is the yield gains we achieved from the Green Revolution. It was not clear in the 1950s that food production could ever meet the needs of a growing population, and hyperfocusing on production was a semi-reasonable strategy. I agree that major changes are needed in the future. Continuing the productivist strategy greatly costs our environments, social systems, and health. A holistic alternative is needed, but we would not be in this position if it were not for the solid foundations we have because of the Green Revolution. Was it a categorical success? No, MANY things could have gone better to meet the needs of rural smallholders, women, the poor, and the environment. But major gains in food security had been won during it. Its mistakes and oversights have done major damage, but humanity would be in a worse position without it.

For the productivists, there is a propensity to treat the Green Revolution as a panacea in the history of humanity and a template for combating hunger into the future. They oversell the successes and sweep the failures under the rug as anti-science activism. In my view, this unwillingness to address these criticisms is cowardly dogma and not scientific curiosity. Additionally, the Green Revolution package is highly profitable. Much of the drive for a GR 2.0 seems to come from organizations with vested interests in selling seed, inputs, and machinery to those last untapped markets.11 Technology is absolutely part of the solution, but blindly introducing new tech and methods into a social template that is not geared towards implementing solutions by and for the average citizen of developing nations will not lead to truly sustainable development. Economic, social, and environmental justice must be at the forefront, not a secondary concern.

So what is to be done? From my point of view, agroecology is a key philosophy that holds promise for the future of agriculture.12 One part academic discipline, one part social movement, and one part a set of farming practices, this approach attempts to balance the need for productivity while serving the needs of people and ecosystems. Instead of pumping fields full of synthetic fertilizer, legume, manure, and conservative use of synthetics can be used to meet fertility needs. Instead of blanketing crops with pesticides, integrated pest management (where chemical agents are a last resort) can be used to manage insects and weeds. Instead of repeatedly planting the same wheat variety for ten seasons, a more diverse planting of both widely and locally adapted varieties can be planted, intercropped or rotated with legumes, to ensure biological and dietary diversity while meeting caloric needs.

A world where the hungry are fed with thriving ecological and social systems is possible. Lessons from the Green Revolution can be useful to see this vision through, but new innovations must be integrated if we are ever to see a world with zero hunger.

For those interested in further reading on the Green Revolution, I cannot recommend enough Noel Veitmeyer's Our Daily Bread, a great biography on Dr. Borlaug detailing the course of this history through his eyes. For more critical pieces, Marci Baranski’s The Globalization of Wheat is an excellent dive into the methodological weaknesses of wide adaptation and the trap modern agricultural development falls into by solely focusing on one strategy. Finally, Raj Patel’s essay The Long Green Revolution, published in the Journal of Peasant Studies, is essential reading on the political economy of the Green Revolution and its limits as an agricultural development approach for the 21st century.

What I’m Reading, Watching, and Listening too

Musician Tries To Change His Identity And Fails: Apparently, Garth Brooks attempted to launch an emo alter ego in the late 90s.

Morocco is Full of Cats: Ruminations on the relationship between communities and their street cats, which “aren’t pests. But they also aren’t truly pets.”

Does Biden Welcome Their Hatred?: A well-written stock-take of the current administration’s anti-trust policy, which I would argue is one of Biden’s most underrated accomplishments (still a mixed bag, of course).